How do you defeat an extra-terrestrial monster, when bullets, torpedoes, missiles and lasers have failed?

With Japanese style professional wrestling moves, of course.

(disclosure: This was my favorite show as a kid.)

Part I:

Part II:

Part III:

· Almost half of all lovers are worse at predicting their partner's heart's desire than a stranger who simply uses average gender-specific preferences.

· In addition, the more you know about your inamorata, the worse your success rate is likely to get.

These cheerful holiday tidings are brought to you by "Why It Is So Hard to Predict Our Partner's Product Preferences: The Effect of Target Familiarity on Prediction Accuracy," in the December issue of the scholarly Journal of Consumer Research, published by the University of Chicago Press

And there's more to it than the cliché of getting your partner the gift that YOU want. (although that's a big part of it) In the article they talked about one guy who got is partner a bathroom scale as a gift. I imagine that his thought process must have been something like "Well she's always talking about her weight. I bet she'd really like a fancy new scale.

But what does any of this have to do with mad scientists or Jonathan Coulton, you ask? It's the JoCo song Skullcrusher Mountain. The song is about an evil-genius/super-villian who falls in love with the girl he's holding captive. My kind of guy! In the song, the protaganist is surprised when his beloved doesn't like the gift he got her.I made this half-pony half-monkey monster to please you

But I get the feeling that you don’t like it

What’s with all the screaming?

You like monkeys, you like ponies

Maybe you don’t like monsters so much

Maybe I used too many monkeys

Isn’t it enough to know that I ruined a pony making a gift for you?

"Nobody in their wildest dreams expected this. But you have a female dragon on her own. She produces a clutch of eggs and those eggs turn out to be fertile. It is nature finding a way," Kevin Buley of Chester Zoo in England said in an interview.

He said the incubating eggs could hatch around Christmas.

The process by which this happens is called parthenogenesis. From Wikipedia:

Parthenogenesis is distinct from artificial animal cloning, a process where the new organism is identical to the cell donor. Parthenogenesis is truly a reproductive process which creates a new individual or individuals from the naturally varied genetic material contained in the eggs of the mother. A litter of animals resulting from parthenogenesis may contain all genetically unique siblings. Parthenogenic offspring of a parthenogen are, however, all genetically identical to each other and to the mother, as a parthenogen is homozygous.

What this means is that the genome is not passed down whole as in cloning; The cells begin meiosis normally by fusing and shuffling their chromosomes, but instead of dividing into two separate haploid egg cells, they stay together essentially fertilizing themselves. The Wikipedia article has even been updated to include Komodo dragons.

Recently, the Komodo dragon which normally reproduces sexually was found to also be able to reproduce asexually by parthenogenesis. [3] Because of the genetics of sex determination in Komodo Dragons uses the WZ system (where WZ is female, ZZ is male, WW is inviable) the offspring of this process will be ZZ (male) or WW (inviable), with no WZ females being born. A case has been documented of a Komodo Dragon switching back to sexual reproduction after a parthenogenetic event. [4]. It has been postulated that this gives an advantage to colonisation of islands, where a single female could theoretically have male offspring asexually, then switch to sexual reproduction to maintain higher level of genetic diversity than asexual reproduction alone can generate. [5] Parthenogenesis may also occur when males and females are both present, as the wild Komodo dragon population is approximately 75 per cent male.

The Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS) was designed to address these questions. The autonomous EITS is a programmable, battery-powered camera and recording system that can be placed on the sea floor and left for 24 to 48 hours to observe the animal life in the dark depths with as little disturbance as possible. It uses far red light illumination that is invisible to most deep-sea inhabitants and an innovative electronic lure that imitates the bioluminescent burglar alarm display of a common deep-sea jellyfish.

The very first time this lure was used it attracted a large squid that is so new to science it can not be placed in any known family.

The article on confabulation repeats a logical fallacy (7 October, p 32). "The idea that we have conscious free will may be an illusion," writes Helen Phillips, because a 1985 experiment "suggested that a signal to move a finger appears in the brain several hundred milliseconds before someone consciously decides to move that finger".

This is silly. The process of making a "conscious decision" to act is obviously not a single event. Factors for and against action must be weighed up, inhibitions must be overcome, environmental constraints must be checked, the muscular signals must be planned so that the action is properly coordinated, and so forth. That fact that somewhere along this complex pathway a signal can be measured indicating movement of a finger is imminent is quite unsurprising. The fallacy lies in inferring that the sensation of "conscious decision" that appears later on is thus illusory or "faked".

We sense all things in a delayed fashion. Our conscious recognition of a flash of light, for example, occurs well after the light actually flashes. Why should the sensation of our own consciousness be any different?

And if we have no free will, then why even bother producing the fake sensation of consciousness after the fact? If we, the conscious entity, could not exert any free will over what our body will do in the future, then our body would presumably conserve energy by simply turning out the lights.

With the exception of his last paragraph, this pretty much describes my view. We are essentially autonomous robots with sensations--including the sensation of our own thoughts.

Dr Walker, who was struck by a bus and a truck in the course of the experiment, spent half the time wearing a cycle helmet and half the time bare-headed. He was wearing the helmet both times he was struck.

He found that drivers were as much as twice as likely to get particularly close to the bicycle when he was wearing the helmet.

...

“By leaving the cyclist less room, drivers reduce the safety margin that cyclists need to deal with obstacles in the road, such as drain covers and potholes, as well as the margin for error in their own judgements.

“We know helmets are useful in low-speed falls, and so definitely good for children, but whether they offer any real protection to somebody struck by a car is very controversial.

“Either way, this study suggests wearing a helmet might make a collision more likely in the first place.”

But why would this be so?

Dr Walker suggests the reason drivers give less room to cyclists wearing helmets is down to how cyclists are perceived as a group.

“We know from research that many drivers see cyclists as a separate subculture, to which they don’t belong,” said Dr Walker.

“As a result they hold stereotyped ideas about cyclists, often judging all riders by the yardstick of the lycra-clad street-warrior.

“This may lead drivers to believe cyclists with helmets are more serious, experienced and predictable than those without.

“The idea that helmeted cyclists are more experienced and less likely to do something unexpected would explain why drivers leave less space when passing.

That actually makes some sense. I know that when I ride on the public bike (and multi-purpose) paths, I always give extra space to unhelmeted riders (or riders with cellphones, ipods, etc.). Although I can usually gauge a cyclist's bike handling skills by simply watching them ride for a second or two.

I'm still a believer in helmets most of the time, but if I'm just making a quick trip to the store, I'll generally pass on the foam hat. My own philosophy is that I always wear a helmet when I'm donning lycra (~90+% of my riding). If I'm out of uniform, the helmet is optional. This fits in well with Dr. Walker's findings. His conclusion is quite apt.

“The best answer is for different types of road user to understand each other better.

“Most adult cyclists know what it is like to drive a car, but relatively few motorists ride bicycles in traffic, and so don’t know the issues cyclists face.

“There should definitely be more information on the needs of other road users when people learn to drive, and practical experience would be even better.

“When people try cycling, they nearly always say it changes the way they treat other road users when they get back in their cars.”

Now what about obeying traffic laws? According to your driver's manual, a bicycle on the road is a vehicle and must obey all the same laws that automobiles follow. I'm sorry but that's just ridiculous. (coalition heads spinning) First, that statement isn't technically true: all motorists must be licensed. Second, the vast majority of those laws were not written with bicycles in mind. Some of the traffic rules seem absolutely preposterous for a vehicle that can travel in the shoulder. Others make no sense for a vehicle that weighs under 200 pounds.

I generally use my own judgement as to when to obey and when not to. I think that I'm actually riding safer when I use my acumen rather than following motorist's rules. I realize that that's just based on gut feeling and anecdotes, but they come from at least ten years experience riding almost every day. And Coturnix thinks that even cars are being safer when negotiating traffic rather than acting like automatons.

Seed Magazine has an article by Linda Baker about how some cities (like Portland--rated the best cycling city in the USA) are even taking some of those rules away in order to make the roads safer.

Portland's so-called "festival street," which opened two months ago, is one of a small but growing number of projects in the United States that seek to reclaim streets used by cars as public places for people, too. The strategy is to blur the boundary between pedestrians and automobiles by removing sidewalks and traffic devices, and to create a seamless multi-purpose urban space.

Combining traffic engineering, urban planning and behavioral psychology, the projects are inspired by a provocative new European street design trend known as "psychological traffic calming," or "shared space." Upending conventional wisdom, advocates of this approach argue that removing road signs, sidewalks, and traffic lights actually slows cars and is safer for pedestrians. Without any clear right-of-way, so the logic goes, motorists are forced to slow down to safer speeds, make eye contact with pedestrians, cyclists and other drivers, and decide among themselves when it is safe to proceed.

Now I'm not advocating riding like a bicycle messenger--those guys are crazy! But seriously, messengers are probably some of the best cyclists out on the road. They are experts at negotiating city traffic. (Another myth is that bicycling in the big city is more dangerous than out in the suburbs. Quite the contrary is true. There are several reasons for this, but the most important is that city motorists expect to see bikes. A suburban motorist who isn't expecting bikes, can look right at a cyclist and not "see" him. Then after the accident say "He came out of nowhere!" City drivers know cyclists are entitled to share the road. In all my years of city cycling, I've never had a motorist scream "Get off the fucking road!"--the same cannot be said for the suburbs.) They (messengers) use their judgement just like I do, albeit with different lines they don't cross. When you see a messenger riding like he's oblivious to all the traffic around him, remember that he sees more than you. For example, while an automobile driver is contained inside a box at least two meters behind the front of the vehicle, a cyclist is only a foot or two from the front of his vehicle and out in the open with full use to his peripheral vision.

In the following video of a 2004 New York City bike messenger race, you get to see them in action. The first time I saw this, I thought they were all lunatics. But the more I watch it, the more I recognize how skilled they are. For example, while it may seem that they are recklessly blowing through red lights, if you pay careful attention, you'll see that they are following each others cues as well as running interference for each other. And remember that the helmet-cam doesn't have the same perspective and peripheral vision that the cyclist does. In fact, the most dangerous thing I saw was the guy coming off the bridge without brakes and with his feet off the pedals. (I also wouldn't recomend getting stoned right before you go riding.)

Welcome to the jungle!

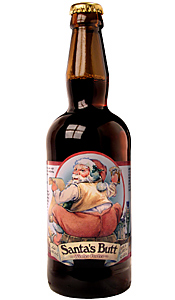

But the state says it's within its rights. The label with Santa might appeal to children, said Maine State Police Lt. Patrick Fleming. The other two labels are considered inappropriate because they show bare-breasted women.

"We stand by our decision and at some point it'll go through the court system and somebody will make the decision on whether we are right or wrong," he said.

Maine also denied label applications for Les Sans Culottes, a French ale, and Rose de Gambrinus, a Belgian fruit beer.

Les Sans Culottes' label is illustrated with detail from Eugene Delacroix's 1830 painting "Liberty Leading the People," which hangs in the Louvre and once appeared on the 100-franc bill. Rose de Gambrinus shows a bare-breasted woman in a watercolor painting commissioned by the brewery.

In a letter to Shelton Brothers, the state denied the applications for the labels because they contained "undignified or improper illustration."